Everything I learned from Tom Petty

What follows is a personal commentary on Tom Petty’s legacy from SMI Jr. Partner and Co-Editor, Christine Mitchell.

The sudden passing of Tom Petty this week hit me like a swift kick to the gut. It was compounded by the fact that I was sitting in a hospital room with my family, my father having had a heart attack overnight as well. Seconds after reading the news on my phone, a heart surgeon pushed the curtain to the room aside to inform us that my dad would need open heart surgery. Petty and my father are the same age. My dad has been there for me my entire life, and, in a very real way, Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers have been as well.

I grew up on Petty’s music and I listen to it still, almost every single day. My parents owned all of his records and played them constantly. I would sit on the floor between the ages of five and twelve and pore over the record jackets and inserts. I memorized every lyric. I learned what verses, choruses, and bridges were from the liner notes. The Heartbreakers were the first band where I knew all of the band members’ names and also the names of the producers and engineers. I didn’t really understand what Jimmy Iovine actually did, but he seemed pretty important. I spent hours staring at the Flying V poster inside of Hard Promises, and studied every album’s band portrait multiple times.

We followed the band through format changes. Everything up to Southern Accents was experienced on vinyl, Accents on tape, and then everything from Let Me Up, I’ve Had Enough was on compact disc. We had to return Let Me Up to Fred Meyer twice until we got a clean copy; CD manufacturing wasn’t quite up to snuff yet.

I learned a lot about love from Tom Petty. Love could be sublime (“The Waiting,” “I’ve Got a Thing About You”), and it could be fucked up (“You Tell Me,” “You Got Lucky,” “A Woman In Love (It’s Not Me)”). Petty would cast himself as the jerk sometimes (“Honey don’t walk out/I’m too drunk to follow,” he sings on “Rebels”). At other times he’d wax nostalgic about loves lost to tear-jerking effect (“The Best of Everything,” “Louisiana Rain”). And Petty loved the South, where he was born and raised. I learned to hold my home close to my heart, too.

I reveled in the weirdness of the characters that inhabited Petty’s songs, and there were many. Who was Speedball in “Something Big,” and what the heck was he up to in that hotel room, calling down to the night clerk for a drink and then needing an outside line? I felt sorry for Spike, the poor punk getting heckled by Petty just for walking into the wrong bar. “Kings Road” is full of folks with “socks and shirts and underwear/that I’d seen before, but I don’t know where,” not to mention a Pakistani man. This doesn’t even touch the videos; Alice the sheet cake being freakily eaten by Petty the Mad Hatter during “Don’t Come Around Here No More,” the steampunk Heartbreakers of “You Got Lucky,” or the cornball “hey, making videos is weird” feel of “Letting You Go” all served to showcase a goofy, slightly twisted thread of humor that winds directly back into the music.

But that was another thing that was great about Tom Petty. He would go out on a limb and put out a pseudo-concept album like Southern Accents, with three way-out-there tracks produced by The Eurythmics’ David Stewart slapped up against classic sounding Heartbreakers songs and then the maudlin, sparse title track. And it actually works. It hangs together. He crawled out on another limb with ELO’s Jeff Lynne to create his first solo album, Full Moon Fever, and we all know how that turned out. Even his work with The Traveling Wilburys is one of those cult classics, although, with four other icons of rock involved, can it really have a “cult” following?

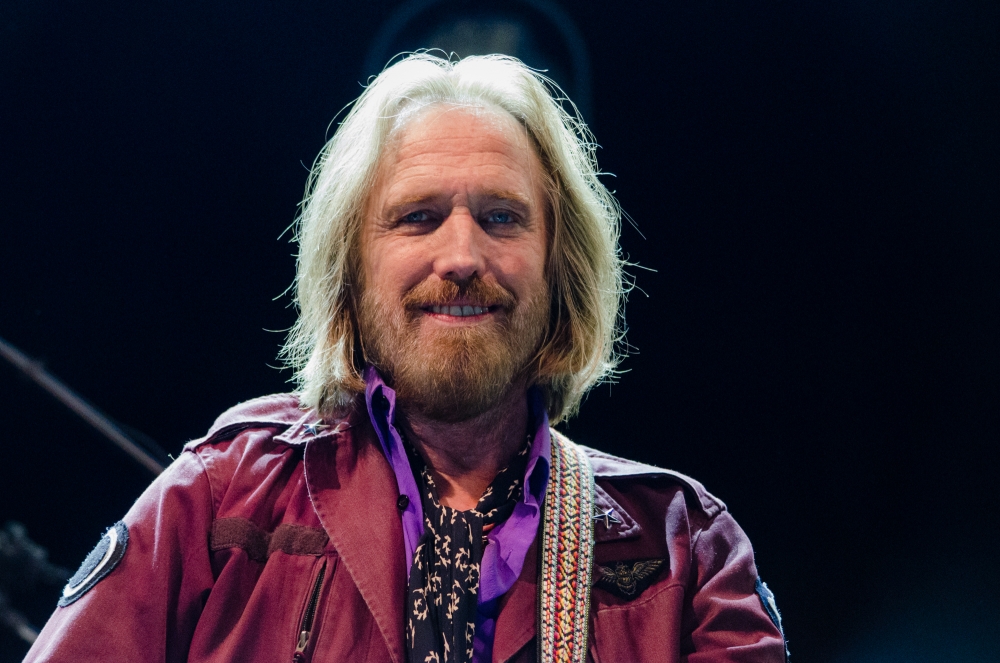

Petty’s reputation live was irreproachable. He held the crowd in the palm of his hand during every show for decades. I was lucky enough to see him perform twice at The Gorge. It was perfect.

Tom Petty cared about making great music. He cared about getting it out to his fans and not getting yanked around by his record label. He had integrity and creativity in spades. His music was popular perfection; he didn’t break the rules, he flourished as he colored inside the lines, and showed those who came after him how it was done. He didn’t sound like anyone else, yet he’s ubiquitous.

My father’s surgery is tomorrow. I won’t tell you his story; he’s still writing it (I hope it’s a long one.) And, truth be told, Petty’s story carries on as well. I carry it in my DNA, practically. I’ll carry him with me for the rest of my own days. Tom Petty is the reason I sit here today and write. He’s the how of how I fell in love with rock n roll.

0 comments