You never forget your first Rush!

Rush performs at Seattle Center’s KeyArena. (Photo by Jimmy Lovaas / jimmylovaas.com)

SMI contributor, Harrison Mains, reflects on his first Rush Concert that took place at Key Arena on November 13th 2012.

I had seen live footage, memorized the records, and watched the documentaries. I had learned to play the songs, I had sung my throat raw, I had even seen I Love You, Man. Still, nothing could prepare me for my first actual Rush concert. The first thing I noticed when I entered the Key Arena was that there were an enormous amount of people there. It seemed everyone and their mother had been brought up on, thoroughly enjoyed, and bought tickets to see Rush. I spent half an hour in line for t-shirts, defeating the purpose of buying before the show, which I do to avoid the rush. (Cue CSI: Miami theme.) I sat down in my seat and watched the people pile in, a more enthusiastic crowd than I had ever seen before. There were scattered whoops and hollers on the crowd as the start time rolled past, ten or fifteen minutes going by (these things never start on time), but finally, the house lights went down.

For photos of the concert go here

We (the vast community of manic Rush fans) were greeted by a hilarious video, revealing that “backstage,” the band was warming up in an unusual way. Virtuoso guitarist and most underrated member Alex Lifeson was being inflated by a scientist, while bassist, lead singer, and keyboardist Geddy Lee was having his neck stretched out, and widely considered best-drummer-in-the-universe and primary lyricist Neil Peart was literally being constructed from mechanical parts, while a single hand on a plate sat spinning a drum stick. Finally, the lights flashed, and there they were. Rush had taken the stage, which was decorated with glowing balls, steampunk devices, and a captivating light show.

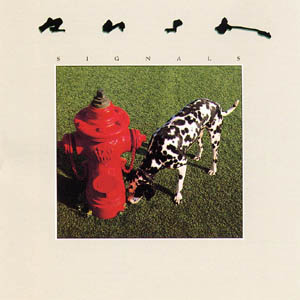

They opened with their song Subdivisions, a well-known and well-loved song among Rush fans about the hurtful way that high school treats those who express individuality. Admittedly, the sound was not great for the first couple of songs. I had to figure out which sounds were guitar and which were keyboard, which was a source of creative disagreement between Lee and Lifeson during Rush’s synth-heavy 80’s albums. I could also barely hear the bass, which is a shame, since I believe that Geddy Lee is the most talented bassist alive. This was also a problem with the synthesizers, as many hard rock fans were turned off of Rush albums like Power Windows, Signals, and Grace Under Pressure, because of the pop-oriented sound and lack of Lee’s signature bass-playing brilliance.

They opened with their song Subdivisions, a well-known and well-loved song among Rush fans about the hurtful way that high school treats those who express individuality. Admittedly, the sound was not great for the first couple of songs. I had to figure out which sounds were guitar and which were keyboard, which was a source of creative disagreement between Lee and Lifeson during Rush’s synth-heavy 80’s albums. I could also barely hear the bass, which is a shame, since I believe that Geddy Lee is the most talented bassist alive. This was also a problem with the synthesizers, as many hard rock fans were turned off of Rush albums like Power Windows, Signals, and Grace Under Pressure, because of the pop-oriented sound and lack of Lee’s signature bass-playing brilliance.

After a few tunes, the band relaxed, and Lee was able to address the audience. He said the band was, “glad to be in the Northwest again,” and that they brought with them, “way too many songs.” Towards the end of their first set, they played one of their instrumentals, Where’s My Thing? The bass was much easier to hear, and the sound was considerably better. I appreciated the switch from synth-based to rock-oriented, and I was amazed at the band members’ enduring musical abilities. In the middle of the song, the audience was treated to another Rush concert staple, the Neil Peart drum solo. Often regarded as one of the finest concert drum soloists of all time, Peart showed his chops by tearing the solo apart effortlessly, making jaws drop all over the stadium. Peart kept interest for several minutes before the rest of the band returned to finish the song. After one more number, Lee told the crowd that they had to take a short break, “due to the fact that we are a million years old.”

LEGENDARY DRUMMERS MICHAEL SHRIEVE AND NEAL PEART GO ONE ON ONE

After the intermission, the crowd was greeted by a short movie, in which what I believe was an IRS worker, played by who I believe was Jay Baruchel, coming to see someone named The Watchmaker. He instead comes across three gnome-like creatures played by the band members themselves. The gnomes teased and tormented the tax collector as he ran through the vast and mysterious chambers of their home, and soon, the band came out and broke into Caravan, the first track off their latest album, Clockwork Angels. This is where the show started to take off, as each band member’s instrument could be heard clearly while a string ensemble accompanied them.

As they progressed (no pun intended) through the album, they employed several special effects that really added to the experience – a difficult feat. There were large spurts of fire that you could feel from the back of the stadium, fireworks that made everyone jump, and giant, moving television screens that formed different shapes above the band. Speaking of the band, their performance was unmatched. With age, their skill has remained firmly intact, and they played the complex rhythms and melodies of their new album with ease and grace.

One song that stood out during this run-thru of the album was Headlong Flight. The first single released for Clockwork Angels, Headlong Flight assured many that Rush’s newest effort would not disappoint. The live experience was…something else. It was not of this world. Never before, in my concert-attending history, has my jaw been so cemented to the floor to the point of actual physical pain (that I did not care about). Alex proved himself a composer, not merely a guitarist, and he weaved intricate melodies over the rhythm section. And oh, how the rhythm section played. Geddy’s singing as never before, and in this case, also did not deter him from plucking out complicated basslines that pounded in my ears like vibrations off the walls of some ancient sound chamber. At the point where I believed the stars had aligned and delivered unto me a miracle of a performance, everything came to a halt, and Neil Peart erupted into a drum solo that I can only describe as pure, distilled perfection. It was as though John Bonham and Keith Moon had risen from the grave to play extra beats in between Peart’s masterful repetitive drum strokes. Arms crossing back and forth, utilizing every inch of his kit that was once described by Stephen Colbert as looking like, “a drum factory exploded,” and at the high point of this ecstasy, the rest of the band came roaring back, and they sounded even better than before. It was like a religious experience, true musical nirvana.

After they had finished playing the album, they decided to play some old songs. They started with Dreamline, the first track on 1991’s Roll the Bones. A live staple, the crowd went wild for Lifeson’s extended guitar solo, which rang through the halls like a ghostly wail. At the end of the song, Neil Peart span around to the more electronic part of his enormous, rotating drum kit, and delivered his final drum solo of the night. His hits of the drum heads triggered many sound effects and mysterious sounds, all while an animation played in the background. The animation was of a long, slinky, robotic creature, whose face was a computer screen bearing the image of Peart’s head. The animation was synched perfectly to the drums, and was amusing to watch. That is, until the robot started to break down and collapse as a pair of mechanical arms tore it apart. I can’t say if it was supposed to be symbolic, but it was heartbreaking. I can firmly state that never in my life had I been deeply emotionally attached to a drum solo until that moment. When the solo finished, Rush went into another fan favorite, Red Sector A, the most fan-beloved song about Nazi concentration camps since Captain Beefheart’s Dachau Blues. The harmonic-based guitar riff brought cheers as Rush blew through the song with great emotional force. Geddy Lee inspired the lyrics, as the song is based on his mother’s account of being trapped in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp (his father was actually in Dachau). According to Lee, that song and that concept contributed to the whole feel, as well as the title, of the album it was on, 1984’s Grace Under Pressure.

After the audience waited with held breath, the “Will they play it?” tension thick as the walls surrounding it, Rush delivered the audience from suspense as Peart tapped out the “-.– -.– –..” time signature of arguably one of Rush’s most famous instrumentals, YYZ. If I had to pick a song that best captured Rush’s entire musical being, the very essence of their skill in performing and composition, the one song that takes all of Rush’s talent and squeezes it into less than five minutes, it would no doubt be YYZ. First of all, Alex Lifeson’s guitar playing drips with emotion, the whines and screams of his pinch harmonics matching the chest-tightening intensity of his note-bending instrument domination. Truly one with his instrument, Lifeson’s guitar solo on that song is one of my personal favorites, with its blend of one-handed tapping, hints of Arabian influence, and technical precision and speed. Peart’s drumming on the song is the stuff of legend, his cymbal patterns driving the song along with an infectious groove, while his fills remain as impressive as they are iconic, fans perfectly air-drumming along in the crowd. Geddy Lee’s bass playing on the song is arguably (and the argument has been made) the greatest bass-playing performance of all-time. The melodies of his playing make the bass no mere rhythm instrument, but a staggering example of lead-instrumentation, and at the very most, the most impressive thing anyone has ever done with the instrument. How Lee’s fingers can hit that many notes in the succession that he does is simply alien (I have tried and failed to play it exactly the way he does), and the strength of his hands is frightening to imagine. His bass solos during the bridge of the song constantly make me want to be a better musician, and I’ve heard the song so many times, I could hum every note of his baffling performance. To describe it live is difficult (as I am running out of adjectives), because it was at this point in the show when I succumbed to the Rush fever, abandoned my professional demeanor, and began violently playing every part on invisible instruments. What can be said? The sound was unreal, allowing the bass to pound as hard as the drums while the guitar held everything together. Every note, every ounce of mastery could be heard in the arena, and the crowd was on the brink of insanity.

What put them over the edge was Rush’s closing number, The Spirit of Radio. As Lifeson tapped away at the riff, the crowd devolved into a mob of screaming maniacs. The Spirit of Radio is one of Rush’s absolute best songs, as well as one of the Rush songs that was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame (in the company of Canadian artists such as Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, and shockingly, not Neil Young). It was performed at the ceremony by devoted Rush fan and Primus bassist, Les Claypool. During the live performance, I was struck for the very first time how incredibly well put-together the music is, as well as how deep the lyrics are. Neil Peart stands among the likes of Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull and Roger Waters of Pink Floyd as one of the most thoughtful and intelligent lyricists in rock music, writing such lines in this song as, “All this machinery making modern music/Can still be open-hearted/Not so coldly charted/It’s really just a question of your honesty, yeah, your honesty/One likes to believe in the freedom of music/But glittering prizes and endless compromises/Shatter the illusion of integrity.” In a world of musical personas dominating the airwaves and making people feel like they’re who they want to be at the cost of feeling like who they are, it’s refreshing to know that when nobody talks about things like honesty and integrity in rock music, Rush will be there to do that job. They played through the song like they were just doing their jobs, and the reggae sections in the middle inspired lots of hand clapping and singing along to the lyrics (though a mouthful). When they left the stage, it was to colossal cheers that went on for a few minutes before something happened.

Rush came back out, and wasted no time intensifying the frenzy the crowd had already worked itself into by playing arguably their most famous song, and their definitive piece of music from the 80’s, Tom Sawyer. From the first beat of the drum beat (that Peart himself has claimed is still difficult to play, even for him), the crowd recognized the song, and nearly tore the stadium apart. While not their most technically impressive song (save Neil Peart’s legendary post-guitar solo drum fills), the song reached people with its incredibly catchy hooks, and meaningful lyrics about an individual who deviates from the norm and rejects conformity, such as in the line, “No his mind is not for rent/To any god or government/Always hopeful, yet discontent/He knows changes aren’t permanent/But change is.” Air guitars fingering Lifeson’s solo (that he improvised on the record, and then had to teach himself) changed quickly to air drums as the song steered toward its final stretch, and the band made the last note a big one.

As the song finished, people began to gather up their things and leave, and I, though exhausted from cheering and smiling for the last three hours, felt a little bit empty. They had not played the one I wanted to see. But as I was quickly reminded, Rush is not known to disappoint, and my heart stopped when I heard the electronic wind blow through the speakers, the opening sounds to the Rush song that changed the way I felt about music forever, 2112. The song takes place in the year indicated by its title, in a futuristic society. This seven-part, 20 minute epic is Rush’s greatest musical, lyrical, and conceptual achievement, no contest. When I found this song, I didn’t understand it at all. It was unlike any music I’d ever heard. I could hear every instrument doing something different, unique, brilliant, and I shivered at Geddy Lee’s vocal wail that communicated emotion, intelligence, and carefully crafted theatrics all at the same time. The bass wasn’t just hiding in the background, quietly genius, rather it was on the front lines of the musical landscape, forcing me to appreciate it. The drums were integral to the overall feel, and I could tell that this drumming, the drumming I’d heard only fairy tales about, was just as carefully constructed and composed as any of the other instruments. The guitar appeared to be an afterthought in comparison, but after multiple listens, I studied it enough to find that it was telling its own tale in a mist of effects and unorthodox chord structures, with solos scattered throughout that positively seared my soul. When they began to play, I finally understood the Rush experience. From exposure, to enchantment, to religion, to experience, I finally understood how the entire crowd felt, seeing these heroes onstage, and though they only played three parts of the song, I couldn’t have cared less. I knew the guitar parts, the bass parts, the drum parts, all note for note, and I lost myself in the attempt to pretend play them all simultaneously. I found what I was looking for that night, a band I could look up to, a band I could respect for everything their music stood for, and a band I could feel like even for a few, brief, wonderful moments, I was a part of. Thank you, Rush. You changed my life again.

Read more articles from Harrison here.

Setlist

1st Set

- Subdivisions

- The Big Money

- Force Ten

- Grand Designs

- Middletown Dreams

- Territories

- The Analog Kid

- The Pass

- Where’s My Thing? (with drum solo)

- Far Cry

2nd Set, with Clockwork Angels Strings

- Caravan

- Clockwork Angels

- The Anarchist

- Carnies

- The Wreckers

- Headlong Flight (with Drum Solo)

- Halo Effect (preceded by guitar solo)

- Wish Them Well

- The Garden

- Dreamline

- Drum Solo (The Percusser)

- Red Sector A

- YYZ

- The Spirit of Radio (without strings)

Encore:

- Tom Sawyer

- 2112 Part I: Overture

- 2112 Part II: The Temples of Syrinx

- 2112 Part VII: Grand Finale

0 comments